Koy 2010 Review of Agricultural Policy and Policy Research A Policy Discussion Paper

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Authorities policy and agricultural production: a scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agricultural commodities

Globalization and Health volume 16, Article number:11 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Unhealthy foods and tobacco remain the leading causes of non-communicable disease (NCDs). These are key agricultural commodities for many countries, and NCD prevention policy needs to consider how to influence production towards healthier options. In that location has been petty scholarship to bridge the agriculture with the public wellness literature that seeks to address the supply of healthy commodities. This scoping review synthesizes the literature on government agronomical policy and production in society to one) present a typology of policies used to influence agricultural output, 2) to provide a preliminary overview of the means that impact is assessed in this literature, and three) to bring this literature into conversation with the literature on nutrient and tobacco supply.

This review analyzes the literature on government agronomical policy and production. Manufactures written in English and published betwixt Jan 1997 and April 2018 (20-year range) were included. But quantitative evaluations were included. Studies that nerveless qualitative information to supplement the quantitative analysis were as well included. One hundred and 3 manufactures were included for data extraction. The following information was extracted: article details (due east.one thousand., writer, title, journal), policy details (east.g., policy tools, goals, context), methods used to evaluate the policy (e.g., outcomes evaluated, sample size, limitations), and study findings. 50 four studies examined the touch on of policy on agricultural output. The remaining manufactures assessed land allocation (n = 25) (due east.chiliad., crop diversification, acreage expansion), efficiency (n = 23), rates of employment including on- and off-farm employment (n = 18), and farm income (n = 17) among others. Input supports, output supports and technical support had an impact on production, income and other outcomes. Although there were of import exceptions, largely attributed to farm level allocation of labour or resource. Financial supports were virtually usually evaluated including greenbacks subsidies, credit, and tax benefits. This type of support resulted in an equal number of studies reporting increased production as those with no effects.

This review provides initial extrapolative insights from the general literature on the touch of regime policies on agronomical production. This review can inform dialogue between the wellness and agronomical sector and evaluative enquiry on policy for alternatives to tobacco production and unhealthy food supply.

Groundwork

Agricultural production has been deeply transformed by the forces of globalization. On the 1 manus, export driven agricultural output has significantly increased access to agronomical commodities in inhospitable environments (east.g. the 3 billion bananas consumed in Canada every twelvemonth [1]). These forces have stimulated the ascension in export-oriented crop production in countries around the globe. The effect has been a concomitant dependence on agronomics-directed foreign investment in exporting countries, and nutrient supply in importing countries. Although theories of comparative advantage point to the benefits of this international supply chain, there are numerous associated problems. These include but are not limited to the negative impact of monocropping [ii], including a rise in fertilizer and pesticide employ in foreign investment dependant countries [iii], dependence on health and environmentally harmful crops such as tobacco [4], enhanced vulnerability to ecology and economic shocks [5], the environmental consequences of extensive refrigeration and transportation emissions across large distances [6], and the pressures on agronomical producing governments to avert enforcing strong labour and ecology controls for fear of losing revenue from foreign trade and investment (although in that location is a body of literature suggesting that these standards are actually strengthened through international trade regimes) [7, viii]. These challenges at the intersection of globalization and agricultural production are no more pronounced than in the supply of tobacco and crops used in wellness-harming foods. Both categories of agricultural product are vulnerable to the in a higher place-noted risks and are impacted, and indeed the risks are compounded, past the duel process of efforts to control demand for these products and marketplace instability.

The relationship between government policy and agronomical supply requires assay on multiple levels. The approaches taken by government to agricultural production are shaped by ideas of economical development, economic interests, the prescriptions and requirements of international agencies (such as the Globe Depository financial institution and the International Monetary Fund) and regimes, local ecology conditions, legacies of national and sub-national institutions among others. Research on agricultural production, policy and public health requires attending to all of these factors and efforts to slice together this puzzle into a comprehensive understanding of how these factors intersect. This review focuses on national level policies and programs as one piece of this puzzle with an attempt to situate these policies in the broader international political economy. Every bit a kickoff step in what is hoped volition exist greater attention to agronomics and united nations/healthy commodities as they chronicle to disease burden and wellness more than generally, this review focuses on the national level recognizing that government policy is ane of the more than straight and tangible factors shaping agricultural product. The objective of this scoping review is to identify lessons from authorities policies and programs that take attempted to shift agricultural production in some way, whether this ways policies to enhance ingather production, induce crop substitution or shift to some other type of employment. Specifically we aim to 1) present a typology of policies used to influence agricultural production, two) to provide a preliminary overview of the ways that affect is assessed in this literature, and 3) to bring this literature into conversation with the literature on food and tobacco supply. This information will provide a starting point to systematically enquiry how to shape the supply of healthier agricultural commodities and inform policy dialogue to this end.

Tobacco, food and agriculture

Unhealthy food products and tobacco are 2 of the leading preventable risk factors for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and cancer [nine, ten]. Demand reduction measures have led to steady but uneven declines in tobacco consumption and are commencement to bear witness impacts on the consumption of unhealthy foods such every bit sugary drinks [eleven, 12]. In that location is also growing recognition of the need to complement these demand reduction measures with attention to bug pertaining to supply. Governments have long been involved in supporting and influencing agricultural production, mainly to support farmer livelihoods and food security. For example, 40% of maize traded on the global marketplace is produced in the U.s. due to heavy subsidies to maize growers [13]. More recent recognition of the pregnant cost posed past non-infectious disease (NCDs) adds an additional public health dimension to this role of government, with a focus on shaping agronomical production in lodge to foster healthier food supply and reducing harmful products, such every bit tobacco, in the consumer surround [14]. This global public health imperative needs to be underpinned by research conducted in agriculture-related disciplines, yet there has been little application of findings to public health research questions or policy dialogue across sectors. Understanding this prove base will be essential for public wellness policy makers and other stakeholders to formulate effective policy recommendations.

Tobacco and food are important agricultural commodities for many countries and thus farm production is tied up with many policy domains and market forces, making it a complex challenge to address through policy and programs [15]. Added to the claiming of controlling production is that if need remains high, then reductions in production might lead to increases in prices for the commodity, potentially inducing growers to switch back to the production of that article. Nevertheless, production is jump up in the rhetoric of opposition to demand reduction measures past unhealthy production-producing industries such as the tobacco industry [16,17,18]. A strong evidence base and a deep agreement of the theory and practice of agricultural product past wellness advocates is a critical office of overcoming probable political and economic challenges.

The main rationale for reducing tobacco production is that tobacco use remains a leading cause of premature preventable death and morbidity globally [19]. Governments have committed, in Articles 17 and 18 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Command, to actively pursue a policy agenda that supports culling livelihoods for tobacco farmers, direct and indirectly reducing tobacco supply. Other reasons to reduce tobacco production include the harmful consequences of growing tobacco leaf for the health and economic livelihoods of farmers, besides as for the environment [20,21,22,23]. Despite the compelling rationale, implementation of interventions to promote culling livelihoods has proved challenging. The complex political economy of tobacco production requires comprehensive interventions that address the needs of farmers, from the supply of inputs to market place access for alternative crops [24]. Hu and Lee [25] emphasize that "while full-calibration crop exchange for tobacco farming … may not be a realistic goal, at least in the about to medium term, encouraging tobacco farmers to shift to other crops has intrinsic benefits … Governments should invest in the infrastructure that will help the farmers grow and marketplace other cash crops" (pg 48).

Nutrient production has experienced massive shifts in the past century with the rise of agronomical technologies, enhanced refrigeration and transportation systems and nearly importantly the globalization of markets [26]. Global agriculture trade accounts for over 20% of global calorire product [13]. This shift has led to shifts from subsistence to export-driven crop production, which in turn has led to the homogenization of crop product [27]. This homogenization has reduced biological variety in the food system, and "the global agricultural system currently overproduces grains, fats, and sugars while product of fruits and vegetables and protein is non sufficient to come across the nutritional needs of the current population" [28]. Although this shift has been credited with helping to reduce rates of global hunger, the substitution of nutrient rich crops for wheat, rice and maize has contributed to both undernutrition and obesity with concomitant increases in rates of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, specially in low- and centre-income countries (LMICs) [29,30,31,32]. For example, the rise in rates of diabetes in India has been attributed to the movement away from loftier-density, protein-rich legumes towards rice and wheat [32]. Negin and colleagues provided an overview of the shifts in agriculture production in Asia and highlight that in Republic of india, "many of the secondary nutrient grains such as pulses, which are major sources of protein in vegetarian Indian diets, too every bit millets such as sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet, which serve as staples in dryland areas and are rich in micronutrients, were underemphasized" [33]. This is a common observation in countries effectually the world and has led to an emerging consensus that agricultural output requires another major shift towards greater production of fruits and vegetables and nutrient-rich cereals and pulses [34].

Methods

Enquiry question

The enquiry question informing this scoping review is: What types of authorities policies and programs facilitate changes in agricultural product? To answer this question we categorize the types of: 1) policies and programs governments take used to encourage farmers to move out of growing a detail ingather, 2) policies and programs used to encourage farmers to move into growing a particular crop, 3) inquiry methodologies used to appraise these policies and programs and finally to 4) outcomes used to evaluate the policies and programs and finally five) summarize the touch that these interventions have had on agricultural production.

Search strategy

We employ a scoping review methodology using methods developed by Arksey and O'Malley. The primary aim of a scoping review is to provide an overview of published literature in order to identify key trends, approaches used to study a topic or gaps in an area of interest. This approach is distinct from a systematic review that attempts to pool and clarify data from existing studies in order to describe stronger conclusions on a measurable topic of interest. Arksey and O'Malley characterize a scoping review as a type of research synthesis that broadly maps the current literature on a sure topic [35]. Fundamental terms and concepts were developed from previously identified articles on the topic and were grouped into farmer behavior (e.thousand., "crop diversification", "off-farm labour migration") and policy categories (east.k., "subsid*", "price control*"). A academy librarian with expertise in the field of agronomics was consulted for input on key terms and database pick. For consummate search terms delight refer to Tabular array one. The electronic databases SCOPUS and CAB Abstracts were used to locate articles. The search was completed over a 3-month period between March and June 2018. We included articles written in English language and published betwixt Jan 1997 and April 2018 (20-year range). The time frame was sufficient to capture policies and programs implemented in the era of neoliberalism, such as privatization forth the supply chain, the elimination of quantitative restrictions on merchandise and the reduction of other barriers to trade such as tariff reductions, among other policy shifts, which dramatically shaped the governance of agricultural output [36]. Nosotros did non place any restrictions based on geography. Studies from all countries or region were eligible for inclusion.

Article selection

Inclusion criteria consisted of articles that quantitatively evaluated a program or policy that affected farmer decisions, for example, a plan providing subsidized seeds to grow a sure crop. Merely manufactures that present empirical inquiry were included; mainly quantitative evaluations, although some studies nerveless qualitative data (e.chiliad. focus groups) to supplement the quantitative analysis. Nosotros made this conclusion to focus on evaluation researc in order to identify general patterns of policy and plan impact. This decision also contributes to our power to draw methodological lessons (e.g. mutual outcomes and evaluation methods) for future enquiry that attempts to mensurate the bear on of policy and programs on tobacco and food supply.

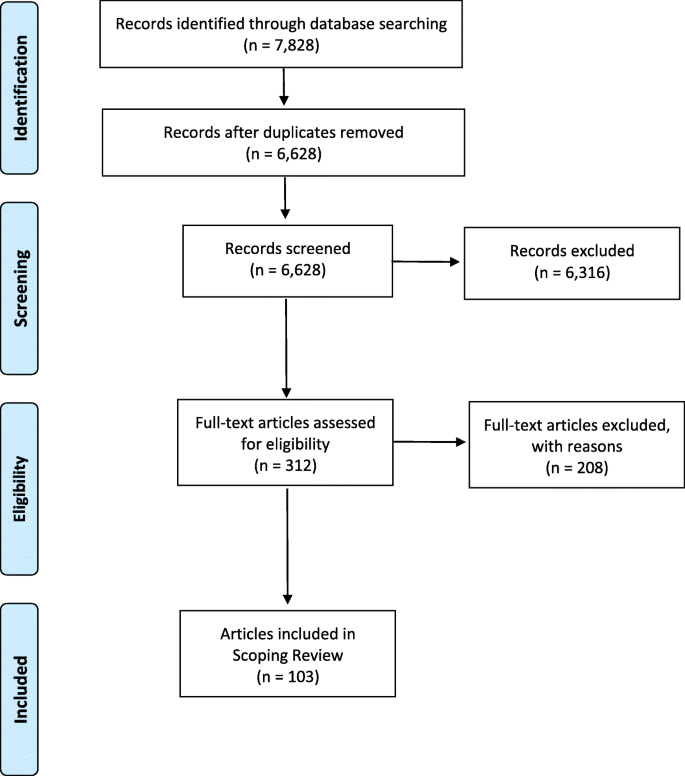

This scoping review strategy involved an initial review of article titles. If the title did non provide sufficient data, the abstruse was then reviewed. Vi thousand iii hundred and sixteen articles were excluded at this phase. Duplicates were also removed at this stage. Commodity abstracts were and then reviewed for full-text consideration. For total-text selection, 3 authors (RL, NP, AA) assessed agreement on the interpretation of the inclusion criteria by independently reviewing the full text of 10 articles. This review resulted in 100% agreement on whether the article would be included or excluded. Ane member continued to review the remainder of manufactures for full-text selection, discussing any challenges with the research team throughout. Figure i illustrates the search and selection procedure using a modified PRISMA flow diagram [37].

Modified PRISMA Flowchart

Information extraction

A data-extraction tabular array was developed by the atomic number 82 author and NP. The information extraction categories were informed by the overarching inquiry question. The following information was extracted from the included manufactures: article details (eastward.g., author, title, journal), policy details (east.yard., policy tools, goals, context), methods used to evaluate the policy (e.thousand., outcomes evaluated, sample size, limitations), and report findings. Two authors (RL, NP) independently reviewed and extracted data from three manufactures, and then compared results. Each article had a possible score of 22 for agreement (number of data columns) with a possible total score of 66 for all three manufactures. The total understanding score was 63/66 or a 95% agreement rate. Discrepancies between the two raters were resolved by a third fellow member of the inquiry team (AA). One member continued to extract the residue of the manufactures.

Results

Descriptive results – policy characteristics

One hundred and three articles were included for full text review. Totals for policy characteristics will differ due to studies being classified under more than one category, or due to studies not reporting on all characteristics. As some articles did not report on all descriptive categories, the post-obit proportions are from those reported. The term intervention volition exist used to refer to both policies and programmes. Articles were categorized into 4 intervention types, (1) input back up, (ii) output back up/restriction, (three) technical back up, and (4) financial support. Table 2 presents definitions of the policy types.

Descriptive results – policy evaluation

Fifty-4 studies assessed production. Of these studies x collected primary data through surverys and interviews, 10 studies used both primary and secondary data and the remaining 34 studies analyzing secondary data. The manufactures identified in this scoping review assessed a wide range of outcomes. Nosotros categorized the outcomes for clarity. The remaining articles assessed land allotment (due north = 25) (e.g., ingather diversification, acreage expansion), efficiency (n = 23), rates of employment including on- and off-subcontract employment (northward = eighteen), and farm income (due north = 17). Other outcomes were measured, such every bit exports, product costs, economic growth, and number of farms, each composing less than five% of the included studies, but together composing 13% (n = 20) of the total. Crops targeted by a policy at times differed from crops targeted by the study. The agricultural product most used to evaluate a policy were cereal crops (37%, northward = 39), followed by oilseed crops (8%, due north = eight), livestock (8%, n = ix), and dairy (8%, n = ix). Less common were agricultural commodities such as fruits, vegetables, and legumes (due east.g., beans, pulses) each comprising less and then v% of the studies but together represented 39% (n = 41) of the total. 30 percent of the evaluations took place less than two years after the intervention (due north = 29) and another 30%, six–x years later on the intervention. A full listing of countries by form is listed in Additional file 1, and a full bibliography of included studies is provided in Additional file ii. For complete information on policy evaluation descriptive information please refer to Table 3 and Table four.

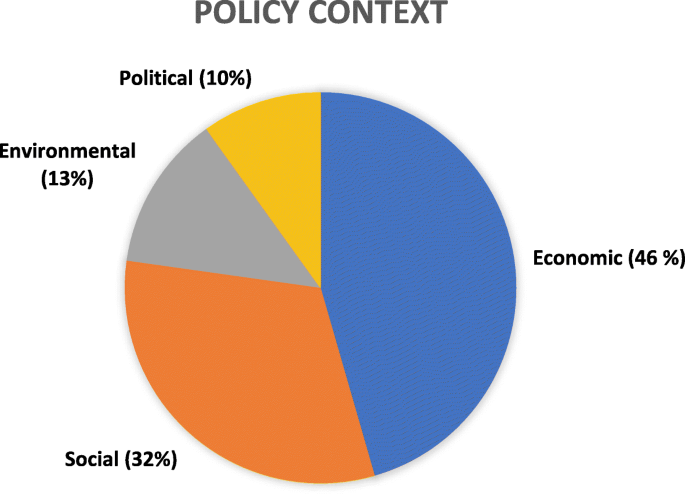

Policy context

Policy and programs are established in particular political, social and economic contexts. Agreement context can contribute to undersanding policy implementation, uptake and impact past identifying policy levers, obstacles and windows of opportunity. We gathered data on the reported economic, political, ecology or social circumstances that were reported as a factor contributing to a alter in policy or programme.

Proportional representation of the context categories reported by the identified articles can exist found in Fig. 2. Many studies reported problems of nutrient security and crop product as a prominent factor contributing to intervention. For case, countries in sub-Saharan Africa have introduced input support programs to address this challenge. Nigeria, for case, found their consumption of rice far exceeded domestic production and the country was relying on plush imports. This situation prompted the government to provide input support measures to farmers such as high-yield seedlings, fertilizers and herbicides to increment the production of rice [38]. A global shift towards market liberalization and away from merchandise-distorting policies was also mentioned past a handful of studies. For case, in 1996, the United States introduced decoupled payments (i.eastward., annual subsidies no longer linked to crop production) aimed at decreasing government involvement in farming decisions, and instead gearing farmers towards more market place-oriented beliefs [39].

Contextual factors shaping government policy

Policy change attributed solely to political circumstances (as opposed to economic and social, for instance) were reported less than others. Of those reported, many involved countries acceding to the EU and thus becoming eligible for the European union Mutual Agricultural Policy support measures, such as Poland in 2004 and Bulgaria in 2007 [forty, 41]. In Poland for case, at that place was an increment in agricultural income in the start few years following their integration with the European union. Alter in government control is another case of a political situation contributing to policy modify, such every bit in the instance of West Bengal, Bharat. In 1977, the Left Front end Coalition headed by the Communist political party of India was voted into power and shortly after, implemented a range of development and welfare policies, one of which was an agronomical input support program of subsidized seeds, fertilizers and pesticides [42].

Many policies were enacted as a response to social circumstances, primarily concerning the welfare of farmers. For instance, after identifying admission to agricultural inputs as a leading challenge for farmers, Republic of zimbabwe implemented a subsidy programme that provided credits via e-vouchers to farmers for purchasing inputs, equally well as coordinated with input suppliers to ensure adequate stock levels and fair prices [43]. Lastly, ecology conditions have increasingly become a prominent commuter for policy change. Due to a rising demand for sustainable fuel sources, governments are introducing policies encouraging the product of bioefuel crops. In 2003, the European Marriage fix targets for the proportion of bioenergy in total energy demand. Information technology was upwardly to each country on how to achieve the targets using methods such equally tax exemptions and production quotas, all of which were expected to encourage farmers to allocate more acreage to biofuel crops [44]. Like to the EU, Brazil in 2004 implemented country-wide targets for biodiesel output. To achieve these goals Brazil used policy tools such as tax and credit incentives for biofuel producers, as well as increased per-sack prices for farmers growing biofuel crops [45].

Impact

Policy type one – input support

A summary of the bear upon of the 4 policies examined is presented in Tabular array 5. Sixteen studies estimated the impact of input support on production (yields and productivity). In nine of these studies [42, 46,47,48,49,l,51,52,53], input back up such as seeds, fertilizer and equipment subsidies, and provision of improved and high quality seeds resulted in an increment in agricultural production. For case, the Malian Fertilizer Subsidy Programme allows farmers to purchase subsidized fertilizer from authorized distributers with the goal of increasing national agricultural production. To evaluate this policy, Theriault et al. (2018) assessed maize and sorghum yields for those who participated in the programme as compared to those who did not participate in the programme and found significantly higher yields for those who participated [54]. Two other studies that examined the bear on of providing input support constitute a negative association between input support and product [55, 56]. This negative association was attributed to redundancy and inefficient employ of resources in the subsidy programme [55] and a lack of data on the amount of actual subsidies received [56]. Other studies identified that the provision of poor quality inputs may account for the lack of effect of input back up programs on product [57]. One report estimated the impact of reducing input subsidies on agricultural production and establish that this resulted in lower productivity [58]. Possebom (2017) on the other manus examined the spillover effect of reducing import tariffs on industrial inputs on other economic sectors. The creation of free trade zones and reduction in import tariffs on industrial inputs led to a decrease in agricultural total production per capita indicating a negative spillover event of this industrialization policy on the agricultural sector. Four studies constitute no effect of input subsidies on production [59,60,61,62]. Also, four studies [43, 51, 63, 64] demonstrated that providing improved subsidized seed and agricultural inputs such as fertilizer led to an increment in farmers' income. Furthermore, three of the four studies that examined the effect of input support on off-subcontract employment plant a positive impact while i plant a negative affect on off-subcontract employment.

Policy type two – output support/restriction

Toll supports, such as counter cyclical payments and cost incentives, were shown to increase product and crop diversification [65, 66]. For example, Alia et al. (2017) assessed the touch of Republic of benin's price support policies on cotton wool production. The policy functioned by government increasing producer prices for cotton by 5% initially and subsequently by 25%. Statistical analysis presented showed that this price back up was associated with an increase in cotton supply, equally the stability of the crop price encouraged more farmers to grow cotton fiber [65]. Two studies evaluated the outcome of market liberalization on commodity of interest and a substitute commodity on production. For instance, Fraser (2006) found that reducing import tariffs (15% reduction) and later on elimination of these tariffs on fruits and vegetables resulted in a reduction in fruit and vegetable production from 15,142 hectors to 13,365 hectors in the local market [67]. Even so an opposite policy of increasing import tarrifs on powdered milk past twoscore% (a substitute for milk) in add-on to price supports for milk led to an increase in the product of 37% [46]. It is important to note that other contextual factors may affect the impact of policies such as trade liberalization. For case, Fraser (2006) institute that international merchandise liberalization contributed to the geographic movement of the vegetable and fruit processing manufacture. As a issue, local producers no longer had a market for processed vegetables which may account for the reduction in vegetables and fruits production observed.

Policy type iii – technical back up

X studies evaluated the effect of technical support on production. Technical support captured a wide range of policy tools such as extension services (e.g., regime sending service workers sharing farming cognition and techniques with farmers), investment in structural evolution (e.g., route structure, rural development), and support in the institution of farming cooperatives. Once more, production and farmer income were the outcomes most evaluated. The touch on of extension services on production were mixed; 3 studies [47, 49, 60] reported an increase in production, and four a subtract or no upshot on production [50, 57, 62, 63]. Higher frequency, quality of services provided, on field practicals and well trained extensions officers were factors associated with a positive bear on of this policy on production. Ross (2017) investigated this human relationship using an experimental design. One group of farmers was provided with agricultural inputs at a subsidized price, another group was provided with the aforementioned packet in improver to extension services including soil fertility management, legume production, in-organic fertilizer and subcontract management methods, and the third control group received no support. It was found that both groups that received an intervention increased total household output, however only the group who received both subsidies and extensions support had statistically significant results [68].

Investment in structural infrastructure such every bit roads and forming of farmer cooperatives were besides shown to increase farm incomes [45, 47, 63, 69]. Combining extension back up with admission to subsidized inputs (e.grand., seeds, fertiliser) was found to be a unremarkably implemented and effective approach. For example, the Native Tobacco Intensification Program in Indonesia, the Agronomics Input Support Programme in Republic of zimbabwe, and the Homestead Food Garden Programme in South Africa all paired input support tools such as garden equipment, seeds, and fertilizer with extension support such every bit training sessions on farming techniques and optimization methods. The studies evaluating these policies all reported increases in the production of their targeted crops, tobacco, tomatoes and maize, respectively [43, 47, lxx]. With the exception of one study, all studies evaluating the effect of extension services, infrastructure and or farmer corporatives on income or farm size reported an increase in farmer incomes or farm size.

Policy blazon 4 – financial support

Financial back up was the most commonly evaluated intervention. Financial support included cash subsidies, credits, revenue enhancement benefits, loan aid and insurance aid. Whereas all three of the previous policy type categories were associated with increases in crop product, financial support had an equal number of studies reporting increased product as studies finding no effects. Also out of 11 studies that examined the impact of financial support on farmer's income and turn a profit, three institute a negative clan. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the touch on of financial back up on farmer's income or revenues is various and dependent on factors such equally farm size and production capacity. For example, Naglova and Gurtler (2016) establish that direct payments improved the farm income and revenue of medium and big scale farms only had a negative impact on smallscale farmer's income. According to Judzinska (2013), the diverse impact of direct payments could be equally a result of the fact that direct payment supports farmers economically and gives them the opportunity to increase their production capacity but at the same time could discourage farmers from improving farm efficiency. This was evident in the fact that out of 27 studies that examined the effect of financial support on efficiency, 19 plant negative or no effect of financial support on efficiency. For case, Straight Income Transfers provided to Greek olive producers as part of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union were institute to have a negative bear on on efficiency, indicating that an increase in payments led to a decrease in efficient farming [71]. Financial support policies have besides been associated with shifts in land allocation such as increases in country allocated to farming, number of farms, crop specialization, and farmer participation. For instance, Galluzzo evaluated a range of CAP direct payments and found that the Single Surface area Payment Scheme had a positive impact on crop specialization, or choosing to grow a certain crop over others [72].

Discussion

This scoping review identified 103 studies that evaluated the impact of input support, output support/restriction, technical support, and financial support on agricultural outcomes. This review finds that much can be achieved at the national level to shape agricultural production, but the national context is tightly bound to global political and economic factors. Start, nosotros found that input supports, such equally subsidies on fertilizers, seeds or farm equipment, mostly resulted in positive changes in production and subcontract income. This finding corresponds with research in the tobacco command literature that finds that inputs are a primal cistron in farmers' decision to enter into contract with leaf buying companies [22, 23]. Second, these findings also signal consistently to the high level of importance of instruction and support for farmers, about often in the form of extension services. The studies that evaluated the impact of education support found positive increases in such outcomes as product and income. This finding also corresponds with cross-exclusive studies in which tobacco farmers identified receiving extension services equally extremely important in supporting their production and livelihoods [73, 74]. 3rd, the findings from this review advise that cost support mechanisms have led to increases in production.

The findings that demonstrate a positive impact of input supports are consequent with general policy shifts away from public support in the agronomical sector (and other public sectors). The absenteeism of input back up from authorities both contributes to and is a result of smallholder farmers inbound into contract with individual companies. These contractual relationships tin can improve product but too concentrate power with individual entitites who then determine the quantity of product purchased, accept power to evaluate the quality of the article and ultimately the cost paid to the farmer [75, 76]. Such contracts often involve inflated prices for inputs and reduced prices offered for the article at market [77, 78]. Tobacco leaf-buying companies can attract farmers to enter into contracts under these unfavourable weather condition considering the arrangement facilitates easier access to inputs, and sometimes besides cash loans, especially when more than traditional credit is scarce [79]. It must be recognised that such private investment is as well probable to limit the operationalization of regime efforts to increase production of healthy agricultural commodities. For instance, where governments accept withdrawn from providing extension services for tobacco, private companies have taken over [73, 74, 80]. In Republic of kenya, the agricultural ministry building does not provide input supports or extension services to tobacco considering the government has listed tobacco as an unscheduled crop, thus taking a hands-off arroyo to tobacco production [73]. Farmers report that services provided by tobacco companies are oft of high quality and they believe that this support contributes to improved yields. This suggests that governments may demand to examine opportunities to curtail individual sector investment in tobacco if alternatives are to be meaningfully pursued.

What complicates this dynamic of regime involvement in providing input back up or subsidies and extension services to smallholder farmers is the full general guidance by key international agencies such as the International Monentary Fund (IMF) for governments to remove subisidies and other public supports. Daoud and colleagues [81] conducted a comprehensive review of IMF policies and found that there is a general push for authorities to remove subsidies although the extent of implementation of this guidance is less articulate. Meurs and colleagues [82] confirm that Imf policy guidance has encouraged or even compelled the reduction of regime expenditure in the agricultural sector in their analysis of the place of IMF policy in Uganda, Tanzania and Malawi. For instance, in Malawi they observe that "policy measures to cutting back expenditures include reducing the budget for maize procurement and agronomical subsidies" among other reductions in public spending. There are important implications stemming from such market-oriented measures that require further written report. What seems articulate is that such market-oriented measures take created a state of affairs where government support for agricultural production will crave deeper ideological shifts in the human relationship between government and market [83].

Certainly if governments are to motion towards promoting agricultural commodities from the standpoint of health and ecology sustainability there will be a demand to develop robust markets for a wider range of commodities. It is an uncontroversial fact that bolt like tobacco or sugar are attractive to farmers because of a combination of factors such every bit access to markets, contractual arrangements that permit admission to inputs and loans, and other facilitators along the supply concatenation [84,85,86]. For example, Natarajan points out that tobacco farmers in South India grow the crop due to its amenability to the environment and the lack of profitable alternatives [87]. Similarly, studies in Malawi and Kenya also observe that farmers go along to abound tobacco, despite limited income, due to a perceived lack of alternatives [22, 23]. This review provides of import direction for research on alternatives. For example, the basic framework presented in this review illustrates the unlike outcomes that tin be examined such as production levels, income, and land allotment. In addition, there are certain policies that demonstrate patterns of effectiveness across different contexts and crops, such as input supports, extension services, and price supports. There is a need to examine how each policy impacts production and farmer decisions and how outcomes are impacted past combined policy approaches. Experiments that effort to shift agricultural production away from tobacco and towards healthy food crops can begin with this typology. As we noted earlier, in add-on to the policies themselves, at that place is a continued need to situate these policies in the broader political economic system and to analyse the processes of policy development and implementation. In that location is clear evidence that merchandise and investment regimes have fostered consumer access to products such as tobacco and unhealthy foods and beverages [88, 89]. These regimes have also facilitated market access and corresponding influence over policy space by these industries. There remains a need to extend the analysis forth the supply chain to examine how such regimes shape production of basic agricultural bolt, and how these regimes interconnect with what is happening at the national and sub-national levels.

The aim of this review is to contribute to future policy and inquiry to affect the supply of healthier agricultural products, including in relation to the pressing demand to shift support abroad from tobacco and unhealthy food crops and towards healthy nutrient crops [90]. In detail, the findings can inform strategic and informed advocacy past wellness actors, equally the policies identified in this review reflect the cadre global approaches to agronomical investment. These policy and programs fall under the purview of agronomical or other ministries with economic development portfolios, and will thus require sensitization of health sector actors to communicate the benefits of intervention in the agricultural supply concatenation for the purpose of health promotion and disease prevention. This reflects previous research indicating that a coherent approach to healthy agricultural product production will involve strategic engagement beyond ministries [91, 92].

This review also suggests that in that location is a stiff evidentiary basis for public health advocacy for input support, provision of extensions services and fiscal support to increase product of healthy food, and government disinvestment abroad from tobacco and towards alternative crops. Information technology is important to develop an understanding of the agricultural policy context. As our review indicates, the role of government in agricultural markets has shifted dramatically since the commencement of the neoliberal era [83]. This shift in some ways has distanced government from direct involvement in the provision of extension and other supports. Policy interventions targeting agriculture are complicated by decades-long shifts in government withdrawal from market activities driven by the neoliberal policy paradigm, and the concomitant primacy of economic considerations in agricultural decision making. The effect of this has been the over-privileging of the function of the private sector either at the expense of authorities participation in the market or perhaps more commonly reorienting regime resource to serve these private interests often at the expense of smallholder farmers [93, 94]. For instance, in Zambia the push button for value-addition along the agricultural supply concatenation, in the absenteeism of a government policy to reduce the tobacco supply, led to government support for tobacco processing and manufacturing [lxxx, 95]. This economic decision will likely lead to increased consumption of tobacco foliage in Republic of zambia, contrary to public wellness objectives. Therefore health advocates must engage with this context to understand what governments can and cannot exercise along the supply concatenation and what types of policies they are more likely to pursue.

Emerging enquiry on alternatives to tobacco has demonstrated that sustained shifts in production crave deep integration with viable culling markets [xx, 96, 97]. It volition be important to evaluate not merely the farm-level indicators such as production and income, but besides broader political economic factors such as market access and trade and investment regimes [15, 98].

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations common to the scoping review methodology. It is possible that the use of additional literature data bases would have yielded farther manufactures. Even so, given the involvement of a specialist librarian it is anticipated that the ii data bases chosen were appropriate to capture the jiff of research on this topic. Considering of the broad scope of the review we did non have the financial resources to extend the search and analysis to the gray literature. There are certainly reports published past government, nongovernmental and intergovernmental agencies that are relevant to this topic. It is hoped that futurity work in this area will draw from these publications. The quality of the methods used in the included studies was not systematically analyzed. However, because the purpose of this review was to identify the latitude of enquiry in this field in order to inform future, more targeted, enquiry on interventions to shape the tobacco and food supply, nosotros think our approach achieved this cease. The relationship between policy and agricultural output may be context dependant and the contextual nature of this relationship requires further systematic exam to determine the policies that are constructive or ineffective across contexts. Final, this review sought to bring the general agricultural literature into conversation with the public health literature on tobacco and nutrient production. However, because different crops have different end uses it is of import that future research rigorously seeks to understand how demand shapes supply. Here we included crops such equally rice, wheat, and others that likely differ greatly from tobacco given the inelasticity of need.

Conclusions

At that place is a demand to apply existing cognition of effective interventions targeting farm production and farm level economic factors. Evaluation studies suggest that certain types of interventions are more effective than others. In that location is also a demand to conduct rigorous evaluation studies on interventions specifically aiming to shape the tobacco and food supply. To date, such research remains deficient.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current written report are available from the respective author on reasonable request.

References

-

Bananas. cftn.ca. 2012. Available from: http://cftn.ca/products/bananas. Accessed 17 Sept 2019.

-

Robinson GM. Globalization of agriculture. Annu Rev Resour Econ. 2018;x(1):133–lx.

-

Jorgenson AK, Kuykendall KA. Globalization, foreign investment dependence and agriculture production: pesticide and fertilizer use in less-developed countries, 1990–2000. Soc Forces. 2008;87(1):529–lx.

-

Smith J, Lee K. From colonisation to globalisation: a history of state capture by the tobacco industry in Malawi. Rev Afr Polit Econ. 2018;45(156):186–202.

-

O'Brien Grand, Leichenko R, Kelkar U, Venema H, Aandahl One thousand, Tompkins H, et al. Mapping vulnerability to multiple stressors: climatic change and globalization in India. Glob Environ Change. 2004;xiv(4):303–thirteen.

-

Ehrenfeld D. The environmental limits to globalization. Conserv Biol. 2005;xix(2):318–26.

-

Bastiaens I, Postnikov E. Greening up: the effects of environmental standards in Eu and US trade agreements. Environ Polit. 2017;26(5):847–69.

-

Davies RB, Vadlamannati KC. A race to the bottom in labor standards? An empirical investigation. J Dev Econ. 2013;103:1–14.

-

Lozano R, Naghavi Thou, Foreman Thou, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease report 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

-

Drope J, Schluger NW. The tobacco atlas. 6th ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018.

-

Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Drink purchases from stores in United mexican states nether the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6704.

-

Briggs ADM, Mytton OT, Kehlbacher A, Tiffin R, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Overall and income specific effect on prevalence of overweight and obesity of twenty% saccharide sweetened drink tax in Uk: econometric and comparative risk assessment modelling report. BMJ. 2013;347:f6189.

-

MacDonald GK, Brauman KA, Sun S, Carlson KM, Cassidy ES, Gerber JS, et al. Rethinking agricultural trade relationships in an era of globalization. BioScience. 2015;65(3):275–89.

-

Lencucha R, Dubé Fifty, Blouin C, Hennis A, Pardon Chiliad, Drager Due north. Fostering the catalyst role of authorities in advancing salubrious food environments. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(6):485–90.

-

Thow AM, Greenberg Due south, Hara M, Friel S, duToit A, Sanders D. Improving policy coherence for nutrient security and diet in Southward Africa: a qualitative policy analysis. Food Sec. 2018;10(4):1105–30.

-

Lencucha R, Drope J, Labonte R. Rhetoric and the law, or the law of rhetoric: how countries oppose novel tobacco control measures at the World Trade Organization. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:100–seven.

-

Kulik MC, Aguinaga Bialous S, Munthali S, Max W. Tobacco growing and the sustainable development goals, Malawi. Balderdash World Health Organ. 2017;95(v):362–7.

-

Otañez MG, Mamudu HM, Glantz SA. Tobacco companies' apply of developing countries' economic reliance on tobacco to lobby confronting global tobacco control: the case of Malawi. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1759–71.

-

Novotny TE, Bialous SA, Burt L, Curtis C, da Costa VL, Iqtidar SU, et al. The environmental and wellness impacts of tobacco agriculture, cigarette manufacture and consumption. Bull Earth Wellness Organ. 2015;93:877–fourscore.

-

Lecours Due north. The Harsh Realities of Tobacco Farming: A Review of Socioeconomic, Health and Ecology Impacts. In: Tobacco control and tobacco farming: Separating myth from reality. Ottawa: Anthem Press (IDRC); 2014.

-

Hurting A, Hancook I, Eden-Green S, Everett B. Research and testify collection on issues related to manufactures 17 and 18 of the framework convention on tobacco control - last total report; 2012.

-

Makoka D, Drope J, Appau A, Labonte R, Li Q, Goma F, et al. Costs, revenues and profits: an economical analysis of smallholder tobacco farmer livelihoods in Republic of malaŵi. Tob Control. 2017;26(half-dozen):634–40.

-

Magati P, Lencucha R, Li Q, Drope J, Labonte R, Appau AB, et al. Costs, contracts and the narrative of prosperity: an economical analysis of smallholder tobacco farming livelihoods in Republic of kenya. Tob Control. 2018;28:268–73 tobaccocontrol-2017-054213.

-

Leppan West, Lecours N, Buckles D. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: Separating myth from reality. Ottawa: Anthem Press (IDRC); 2014.

-

Hu T, Lee AH. Commentary: tobacco command and tobacco farming in African countries. J Public Wellness Policy. 2015;36(one):41–51.

-

Lambin EF, Turner BL, Geist HJ, Agbola SB, Angelsen A, Bruce JW, et al. The causes of land-use and land-cover modify: moving beyond the myths. Glob Environ Modify. 2001;11(iv):261–nine.

-

Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, Ramirez-Villegas J, Guarino Fifty, Jarvis A, et al. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(11):4001–6.

-

Kc KB, Dias GM, Veeramani A, Swanton CJ, Fraser D, Steinke D, et al. When too much isn't enough: does electric current food production meet global nutritional needs? PLoS One. 2018;thirteen(10):e0205683.

-

Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu M, et al. Global, regional, and National Burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;17:23715.

-

Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Sharma Chiliad, Roth GA, Johnson C, Harikrishnan S, et al. The changing patterns of cardiovascular diseases and their take chances factors in u.s.a. of India: the global brunt of disease report 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Wellness. 2018;half-dozen(12):e1339–51.

-

van Dieren S, Beulens JWJ, van der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE, Nealb B. The global brunt of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(1_suppl):s3–8.

-

Tandon N, Anjana RM, Mohan V, Kaur T, Afshin A, Ong 1000, et al. The increasing burden of diabetes and variations amongst the states of India: the global brunt of affliction report 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Wellness. 2018;6(12):e1352–62.

-

Negin J, Remans R, Karuti Due south, Fanzo JC. Integrating a broader notion of nutrient security and gender empowerment into the African Green revolution. Nutrient Secur. 2009;one(3):351–60.

-

Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the Consume–lancet committee on salubrious diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447–92.

-

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):xix–32.

-

Busch L. Can fairy Tales come true? The surprising story of neoliberalism and world agriculture. Sociol Rural. 2010;50(iv):331–51.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

-

Ajani RO, Oluwasola O. Appraisal of upland rice production in southwestern Nigeria: a policy analysis matrix approach. J AgriScience. 2014;4(8):399–408.

-

Peckham JG, Kropp JD. Decoupled direct payments nether base acreage and yield updating uncertainty: an investigation of agricultural chemical use. J Agric Resour Econ. 2012;41(ii):158–74.

-

Judzinska A. The influence of directly support under common agricultural policy of the eu on farm incomes in Poland. Abstruse. Appl Stud Agribus Commer. 2013;7:33–vii.

-

Sokolova E, Kirovski P, Ivanov B. The role of EU direct payments for production decision-making in Bulgarian agriculture. Agric For. 2015;61(4):145–52.

-

Bardhan P, Mookherjee D. Subsidized farm input programs and agricultural operation: a farm-level analysis of W Bengal'southward greenish revolution, 1982-1995. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2011;3(4):186–214.

-

Zivenge E, Jesythomas K. Impact of agriculture input support plan on economic benefit in Zimbabwe. J Commer Jitney Manag. 2014;seven(1):210–4.

-

Gardebroek C, Reimer JJ, Baller Fifty. The impact of biofuel policies on crop acreages in Germany and France. J Agric Econ. 2017;68(three):839–lx.

-

Padula Advert, Santos MS, Ferreira 50, Borenstein D. The emergence of the biodiesel industry in Brazil: current figures and future prospects. Free energy Policy. 2012;44:395–405.

-

Kabir MH, Talukder RK. Economics of modest scale dairy farming in Bangladesh under the government back up plan. Nitis IM, shin MT, editors. J Anim Sci. 1999;12(3):429–34.

-

Andri KB, Santosa P, Arifin Z. An empirical study of supply chain and intensification plan on Madura tobacco industry in East Java. J Agric Res. 2011;vi(1):58–66.

-

FuJin Y, DingQiang S, YingHeng Z. Grain subsidy, liquidity constraints and food security-bear on of the grain subsidy program on the grain-sown areas in People's republic of china. Food Policy. 2015;50:114–24.

-

Herath HMKV, Gunawardena ERN, Wickramasinghe WMADB. The bear on of "Kethata Aruna" fertilizer subsidy programme on fertilizer use and paddy production in Sri Lanka. Trop Agric Res. 2013;25(1):xiv–26.

-

Hosseingholizadeh North, Haghighat J, Mohammadrezaei R. Examining subsidy polices on maize production in Iran (panel data approach). J Agric Manag Dev. 2014;4(3):171–82.

-

Stonemason NM, Smale Thousand. Impacts of subsidized hybrid seed on indicators of economical well-being among smallholder maize growers in Zambia. (special result: input subsidy programs (ISPs) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).). Jayne T, Rashid Southward, editors. Agric Econ. 2013;44(6):659–70.

-

Muncan P, Bozic D. The effects of input subsidies on field crop production in Serbia. Econ Agric. 2013;lx(three):585–94.

-

Sianjase A, Seshamani V. Impacts of farmer inputs support program on beneficiaries in Gwembe District of Zambia. J Environ Issues Agric Dev Count. 2013;five(one):40–l.

-

Theriault V, Smale M, Assima A. The Malian fertiliser value chain post-subsidy: an analysis of its structure and performance. Dev Pract. 2018;28(two):242–56.

-

LiYun 50, GuanQiao L. Efficiency evaluation of upshot of direct grain subsidy policy on performance of rice production. Asian Agric Res. 2017;nine(4):11–five.

-

Lopez CA, Salazar L, de Salvo CP. Agronomical input subsidies and productivity: the example of Paraguayan farmers. IDB Piece of work Pap Ser Inter Am Dev Bank. 2017. p. 1–31.

-

Okoboi G, Kuteesa A, Barungi M. The affect of the National Agricultural Advisory Services program on household production and welfare in Uganda. Res Ser Econ Policy Res Cent. 2013. Working paper 7. 1-38.

-

Hanjra MA, Culas RJ. The political economy of maize product and poverty reduction in Zambia: assay of the last 50 years. J Asian Afr Stud. 2011;46(vi):546–66.

-

Lu WC. Effects of agronomical market place policy on crop production in China. Nutrient Policy. 2002;27:561–73.

-

Onumah JA, Williams PA, Quaye W, Akuffobea M, Onumah EE. Smallholder cocoa farmers access to on/off-farm back up services and its contribution to output in the eastern region of Ghana. J Agric Rural Dev. 2014;four(10):484–95.

-

Ragasa C, Chapoto A. Moving in the right direction? The role of price subsidies in fertilizer use and maize productivity in Ghana. Food Secur. 2017;9(2):329–53.

-

Ragasa C, Mazunda J. The impact of agricultural extension services in the context of a heavily subsidized input arrangement: The example of Malawi. World Development. 2018;105:25-47.

-

Nwachukwu IN, Ezeh CI. Touch on of selected rural development programmes on poverty alleviation in Ikwuano LGA, Abia State, Nigeria. J Food. 2007;7(5):ane-17.

-

Yin R, Liu C, Zhao Grand, Yao S, Liu H. The implementation and impacts of China's largest payment for ecosystem services program as revealed past longitudinal household information. Country Use Policy. 2014;xl:45-55.

-

Alia DY, Floquet A, Adjovi E. Heterogeneous welfare effect of cotton fiber pricing on households in Republic of benin. Afr Dev Rev. 2017;29(two):107–21.

-

D'Antoni JM, Mishra AK, Blayney D. Assessing participation in the milk income loss contract plan and its impact on milk production. J Policy Model. 2013;35(ii):243–54.

-

Fraser EDG. Crop diversification and trade liberalization: linking global trade and local management through a regional case study. Agric Hum Values. 2006;23(3):271–81.

-

Ross M. Leveraging social networks for agricultural development in Africa. PhD Thesis. Wageningen University. Wageningen, Netherlands.

-

Lasanta T, Marín-Yaseli ML. Effects of European common agricultural policy of the eu and regional policy on the socioeconomic development of the Central Pyrenees, Spain. Mt Res Dev. 2007;27(2):130–vii.

-

Bahta YT, Owusu-Sekyere East, Tlalang Be. Assessing participation in homestead food garden programmes, land ownership and their impact on productivity and net returns of smallholder maize producers in South Africa. Agrekon. 2018;57(1):49–63.

-

Zhu 10, Karagiannis G, Oude Lansink A. The impact of direct income transfers of CAP on greek olive farms' performance: using a non-monotonic inefficiency effects model. J Agric Econ. 2011;62(3):630–eight.

-

Galluzzo Due north. Assay of subsidies allocated by the common agricultural policy and cropping specialization in Romanian farms using FADN dataset. Sci Pap Ser Manag Econ Eng Agric Rural Dev. 2016;sixteen(one):157–64.

-

Magati P, Li Q, Drope J, Lencucha R, Labonte R. The economics of tobacco farming in Kenya. Nairobi: Institute of Legislative Affairs; American Cancer Society; 2016.

-

Goma F, Drope J, Zulu R, Li Q, Chelwa G, Labonte R, et al. The economics of tobacco farming in Zambia. Lusaka, Republic of zambia and Atlanta: University of Zambia; American Cancer Society; 2016.

-

Prowse M. A history of tobacco production and marketing in Malawi, 1890–2010. J E Afr Stud. 2013;7(4):691–712.

-

Prowse One thousand, Grassin P. Tobacco, transformation and development dilemmas from Central Africa. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020.

-

Makoka D, Drope J, Appau A, Lencucha R. Subcontract-level economic science of tobacco production in Malawi. Lilongwe: Centre for Agronomical Inquiry and Evolution; American Cancer Social club; 2016.

-

Otanez MG, Mamudu H, Glantz SA. Global leaf companies command the tobacco market in Republic of malaŵi. Tob Control. 2007;xvi(4):261–nine.

-

Niño HP. Form dynamics in contract farming: the case of tobacco product in Mozambique. Third World Q. 2016;37(10):1787–808.

-

Labonté R, Lencucha R, Drope J, Packer C, Goma FM, Zulu R. The institutional context of tobacco product in Zambia. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):5.

-

Daoud A, Reinsberg B, Kentikelenis AE, Stubbs TH, King LP. The International Budgetary Fund's interventions in food and agriculture: an analysis of loans and conditions. Food Policy. 2019;83:204–xviii.

-

Meurs M, Seidelmann L, Koutsoumpa M. How healthy is a 'healthy economic system'? Incompatibility between current pathways towards SDG3 and SDG8. Glob Health. 2019;15(i):83.

-

Lencucha R, Thow AM. How neoliberalism is shaping the supply of unhealthy commodities and what this means for NCD prevention. Int J Wellness Policy Manag. 2019;8(9):514–xx.

-

Appau A, Drope J, Goma F, Magati P, Makoka D, Zulu R, et al. Explaining Why Farmers Grow Tobacco: Bear witness from Republic of malaŵi, Kenya and Zambia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019. https://doi.org/x.1093/ntr/ntz173. [Epub ahead of impress]

-

Appau A, Drope J, Witoelar F, Chavez JJ, Lencucha R. Why do farmers grow tobacco? A qualitative exploration of farmers perspectives in Republic of indonesia and Philippines. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(13):2330.

-

Rahman MS, Ahmed NAMF, Ali M, Abedin MM, Islam MS. Determinants of tobacco tillage in Bangladesh. Tob Cont. 2019; [cited 2020 January 1]; Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2019/11/26/tobaccocontrol-2019-055167.

-

Natarajan N. Moving by the problematisation of tobacco farming: insights from South Republic of india. Tob Command. 2018;27(iii):272–vii.

-

Baker P, Friel South, Schram A, Labonte R. Trade and investment liberalization, food systems modify and highly processed nutrient consumption: a natural experiment contrasting the soft-beverage markets of Peru and Bolivia. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):24.

-

Barlow P, McKee Yard, Stuckler D. The impact of U.South. gratis trade agreements on calorie availability and obesity: a natural experiment in Canada. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):637–43.

-

Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C, Huang TT-K, Costa SA, Ashe M, et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2400–9.

-

Lencucha R, Drope J, Chavez JJ. Whole-of-government approaches to NCDs: the case of the Philippines interagency committee—tobacco. Health Policy Program. 2015;thirty(7):844–52.

-

Drope J, Lencucha R. Tobacco control and trade policy: proactive strategies for integrating policy norms. J Public Health Policy. 2013;34(1):153–64.

-

Hall PA. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: the example of economic policymaking in Britain. Comp Polit. 1993;25(3):275–96.

-

Gill S. Globalisation, market civilisation, and disciplinary neoliberalism. Millennium. 1995;24(3):399–423.

-

Lencucha R, Drope J, Labonte R, Zulu R, Goma F. Investment incentives and the implementation of the framework convention on tobacco control: bear witness from Zambia. Tob Command. 2016;25:483–vii.

-

Magati PO, Kibwage JK, Omondi SG, Ruigu Grand, Omwansa West. A Toll-do good Analysis of Substituting Bamboo for Tobacco: A Case Study of Smallholder Tobacco Farmers in South Nyanza, Republic of kenya. Sci J Agric Res Manag. 2012;2012 [cited 2016 Jan eight]. Bachelor from: http://www.sjpub.org/sjar/abstruse/sjarm-204.html.

-

Kibwage JK, Netondo GW, Odondo AJ, Momanyi GM, Awadh AH, Magati PO. Diversification of Household Livelihood Strategies for Tobacco Pocket-size-holder Farmers: A Case Study of Introducing Bamboo in Due south Nyanza Region, Kenya. 2014 [cited 2018 Jul 31]; Available from: http://repository.seku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/466

-

Appau A, Drope J, Labonté R, Stoklosa M, Lencucha R. Disentangling regional trade agreements, merchandise flows and tobacco affordability in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Health. 2017;13:81.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give thanks the two reviewers for helpful feedback and suggestions.

Funding

This research was supported by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) nether Award Number R01TW010898; and the National Establish on Drug Abuse, the Fogarty International Center and NCI nether Award Number R01DA035158.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

RL conceived of the review. NP conducted the literature search, information extraction and analysis nether the supervision of RL. NP, RL, AA contributed to data extraction and assay. RL and NP wrote the offset draft of the manuscript. JD and AMT contributed to the data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to the preparation of the manuscript. RL led the revisions post-obit peer review with the support of NP. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided yous give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zip/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lencucha, R., Pal, N.East., Appau, A. et al. Authorities policy and agricultural production: a scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agronomical bolt. Global Wellness 16, eleven (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12992-020-0542-ii

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-0542-2

Keywords

- Non-communicable disease

- Food policy

- Agriculture

- Review

- Tobacco

- Tobacco control

- Global health policy

Source: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-020-0542-2

0 Response to "Koy 2010 Review of Agricultural Policy and Policy Research A Policy Discussion Paper"

Postar um comentário